Why wasn't I fired?

Professor Herman and I were friends. I remember a conversation with her from -- I don’t know when, maybe 15 years ago. I told her that my willpower seemed to depend on the time of day. In the afternoon, I had opinions, I had principles, I had a spine. In the morning, I was more pliable.

In the morning, I said, I would agree to anything. In the morning, I would be one of Hitler’s willing executioners.

Herman stiffened. She made a sound of dismay. No, you wouldn’t, she said. You’re not like that.

I understood that my joke had been a false step. Sorry, I said. I’m just trying to be funny.

One thing you can do in this kind of situation is to keep going. That’s what an entertainer might do. There’s humor in playing with boundaries, or in pretending there are no boundaries. March directly into the forbidden zone and keep going until the boundary disappears from view. Keep throwing more speech at the unacceptable target until the sheer quantity of your speech newly defines what is acceptable. Tell five more outrageous jokes until you find one that your listener can’t help laughing at.

Another way to keep going would be to have a conversation about human nature. My joke depended on a misrepresentation of the “willing executioners” theory of the Holocaust. (The theory, which does not seem to be held in high regard by historians, is that the Germans were “eliminationists,” not weak-willed executioners; they were expressing their will by killing Jews.) Perhaps I thought that people in general were capable of astonishing brutality. Perhaps Herman thought that some people were capable of brutality, and others were not. We could have had a conversation about that.

The point is that we were talking like friends. I didn’t hesitate to tell an outrageous joke; she didn’t hesitate to tell me that she didn’t like it. Often in our conversations, the positions were reversed: she said something that pushed one of my buttons, and I said bluntly that I hated it. We had different ideas, values, thresholds. We appreciated those differences. We tested them. We pushed them around. You’re not a morning person? Interesting. You don’t like Holocaust jokes? Interesting.

Certain aspects of yourself, certain thoughts and expressions, only become possible in the company of certain friends. The philosopher Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu) has a story about this. Here is Arthur Waley’s translation:

Once when Chuang Tzu was walking in a funeral procession, he came upon Hui Tzu’s tomb, and turning to those who were with him he said, “There was once a wall-plasterer who when any plaster fell upon his nose, even a speck no thicker than a fly’s wing, used to get the mason who worked with him to slice it off. The mason brandished his adze with such force that there was a sound of rushing wind; but he sliced the plaster clean off, leaving the plasterer’s nose completely intact; the plasterer, on his side, standing still, without the least change of expression.

“Yuan, prince of Sung, heard of this and sent for the mason, saying to him, ‘I should very much like to see you attempt this performance.’ The mason said, ‘It is true that I used to do it. But I need the right stuff to work upon, and the partner who supplied such material died long ago.

“Since Hui Tzu died I, too, have had no proper stuff to work upon, have had no one with whom I can really talk.”

That’s what you lose when a friendship ends.

In 2016, I thought that Herman was my friend. I didn’t know that she had developed a habit of denouncing me in emails that she sent to the dean’s office. But it’s not like I didn’t notice any changes. She bought a house in Altadena; she told me that she was going to have a party, and that I should come. Great, I said. I will be there! I never heard her say anything else about a housewarming party, but at some point the party took place, and at some point I understood that it had taken place. Oh, well, I thought, I guess we’re not as close as we used to be. That’s too bad.

The tone of our conversation changed. I became aware of the change when I tried to send her an email with a link to a recording of a beautiful song from 1926. The subject heading I originally composed was the refrain and title of the song: “I got your ice cold Nugrape.”

I got a Nugrape nice and fine

Plenty imitations but there’s none like mine

I got your ice cold Nugrape

I thought Herman, who studied the history of food, would be interested in a song about a soft drink by a group, the Nugrape Twins, that specialized in spirituals. I also thought she would be interested in the artificial grape flavor of the drink.

I hesitated before sending the email. The subject heading felt off. “I got your ice cold Nugrape.” In the song, the refrain is plaintive, but the words are somewhat aggressive. They could be sexual or violent or both. Like, I have something that you want. Or, I have something that belongs to you. I stole your ice-cold Nugrape and I’m daring you to take it back.

I noted the ambiguous implications of the subject heading. I enjoyed them. Ordinarily I would not have hesitated to activate them in communication with a friend. On this occasion, reluctantly, I had to admit that Herman was a friend of a different type. I could no longer count on her to give me the benefit of the doubt if I said something that offended her. She was the wrong recipient for ambiguous language.

We weren’t as close as we used to be, so our talk could not be as freewheeling as it once was. I revised the subject heading and the body of the message to make them gentle, respectful, and unambiguous.

Subject: you might appreciate this

“I Got Your Ice Cold Nugrape.” Amazing song from 1926 by the Nugrape Twins, a group that specialized in spirituals but had a corporate sponsor, Nugrape (a soft drink, I guess):

If you haven’t heard it, I think you should check it out.

There’s a strange mix of styles in this song, each one of which you can hear pretty clearly. The vocal line and the words have elements of spirituals, blues, and old modal folk tunes. The piano part sounds like 1920s pop music, nothing remotely funky about it. Some of the language is simply advertising but this element doesn’t dominate the others or hold them together.

I can’t tell if this is a general style coming together or breaking apart. Something weird is happening due to commercial pressure.

I also like the spelling of “new” as “nu.”

Her reply indicated that she did appreciate it.

amazing. i mean puzzling and beautiful and confusing.

nugrape twins!!!!!

i'll be looking into this.

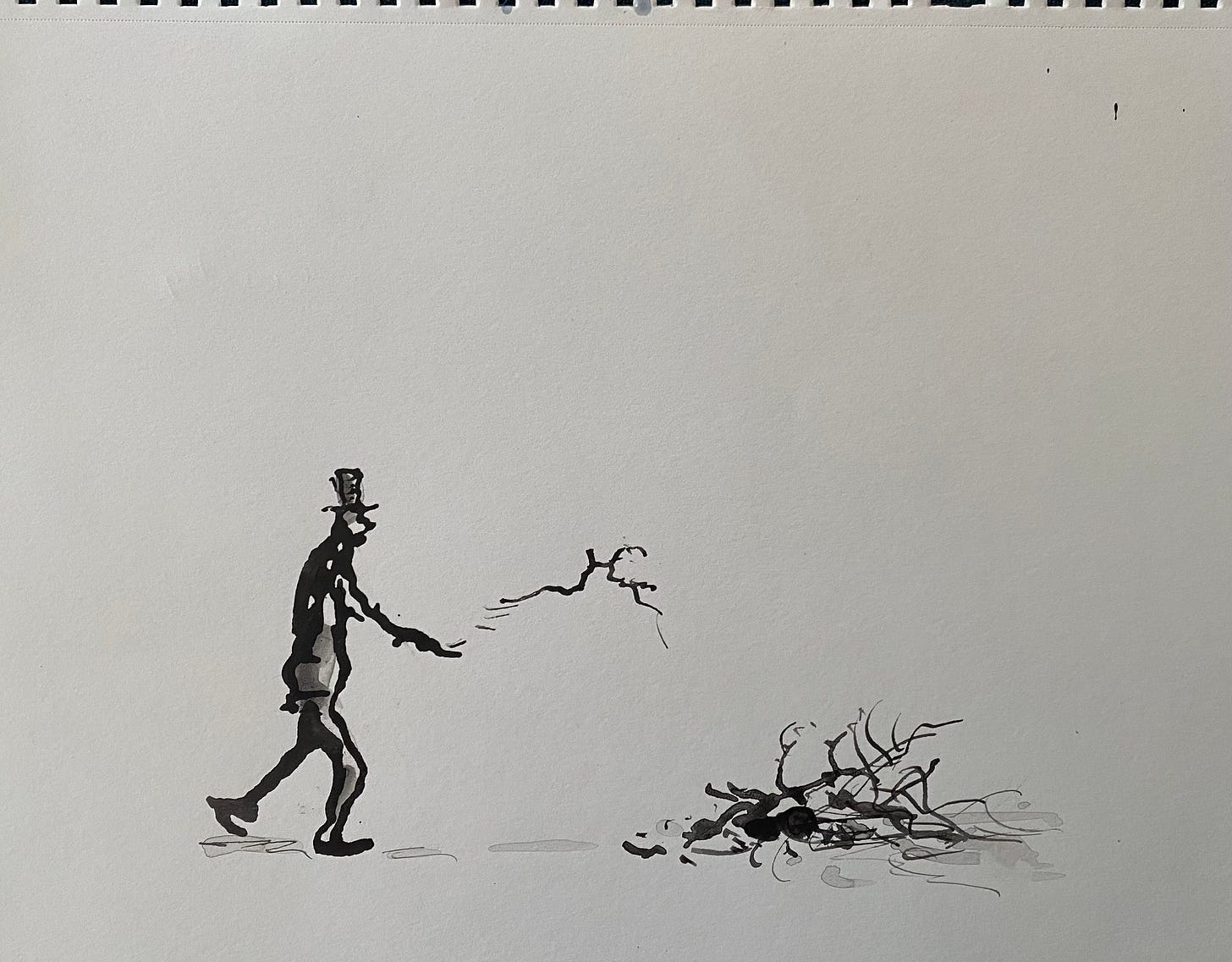

You might say the aggression I enjoyed in the song was in tension with the conventions of professional discourse that I was belatedly learning. Or, when studying art in school, you might say there is always going to be tension between the art and the school. Lionel Trilling says something to this effect: art has no place in school. A college diploma, the good that we sell, is a token of civilization. School is a civilizing process. And art, although it is part of the same process, is not really on the side of civilization. Art is free and savage.

This observation itself returned to haunt me a few years later. Professor Lisa, a poet who had been hired to teach a creative writing workshop, moved into her office in September 2018 and immediately sent me a photograph depicting herself, her whole body, wedged into the bookshelf, beneath the caption, “some of the energies in art are resistant to civilizing.”

Lisa was a talented writer and essentially a barbarian who was capable of behaving appropriately only in the mode of parody. As far as she was concerned, the discursive conventions of the profession were mere toys. When introduced into the alien environment of an office, she started climbing the walls.

Her self-portrait was a good joke on me, because it reminded me of the extent to which I had absorbed the values of a repressive institution (“resistant to civilizing,” forsooth! I was a schoolteacher, a veritable department chair), and because formulating a reply was nearly impossible. What was I supposed to do, read her a lecture about not climbing on the furniture? Or follow her example, take a picture of myself in my office, curled up in the depths of my desk drawer?

I wrote: “Great picture!” I wanted to convey my appreciation of the photograph without making any statement that could be interpreted as a comment on her appearance. An avuncular tone seemed suitable.

But that isn’t the reply I sent. I deleted the exclamation, “Great picture!”, and wrote words of a cooler temperature: “Excellent, just excellent.” No one, myself included, will ever know what I intended to call excellent -- Lisa’s photograph, Lisa’s body, the books on her shelf, the furniture in her office, the caption (my own paraphrase of Trilling), the essay “On the Teaching of Modern Literature” by Trilling, the whole project of resisting civilization?

I wish you could understand what it was like in 2018-2019, the years when I was chair, and 2020, when I was the subject of a workplace investigation. Every day I was assigned twenty puzzles, and the puzzles could only be solved by combinations of words, and it seemed that I might be fired if I chose the wrong words. In 2018, one of my colleagues wanted me to be fired, and she was studying my combinations of words with a view to creating conflicts that could lead me to lose my job. In 2019, the same thing, with the added wrinkle that two of my colleagues wanted me to be fired.

Why wasn’t I fired? It wasn’t because I was good at being chair. It wasn’t because I was socially adept. It wasn’t because I always did the right thing, or always knew what was right. It wasn’t because of the support of my colleagues or the administration of the college. It wasn’t because the college’s policies were consistent or intelligible. It wasn’t because of the protections of academic freedom, tenure, or California law. It wasn’t because of my innocence, or because I never did anything that merited firing, or worse.

I was lucky, that’s all. I think I’ve been very lucky.